Event Program

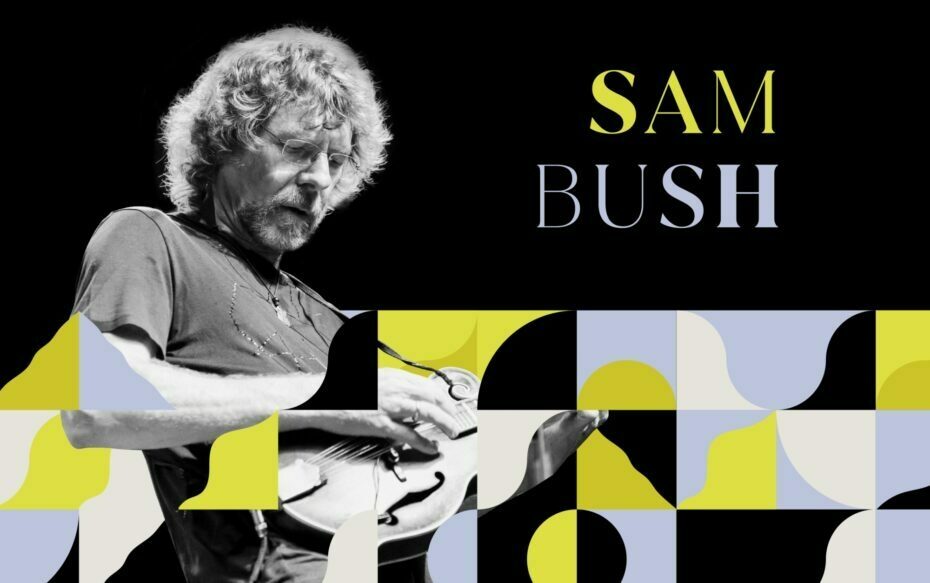

SAM BUSH

SAM BUSH

FRI, OCT 27

TONIGHT’S ARTIST

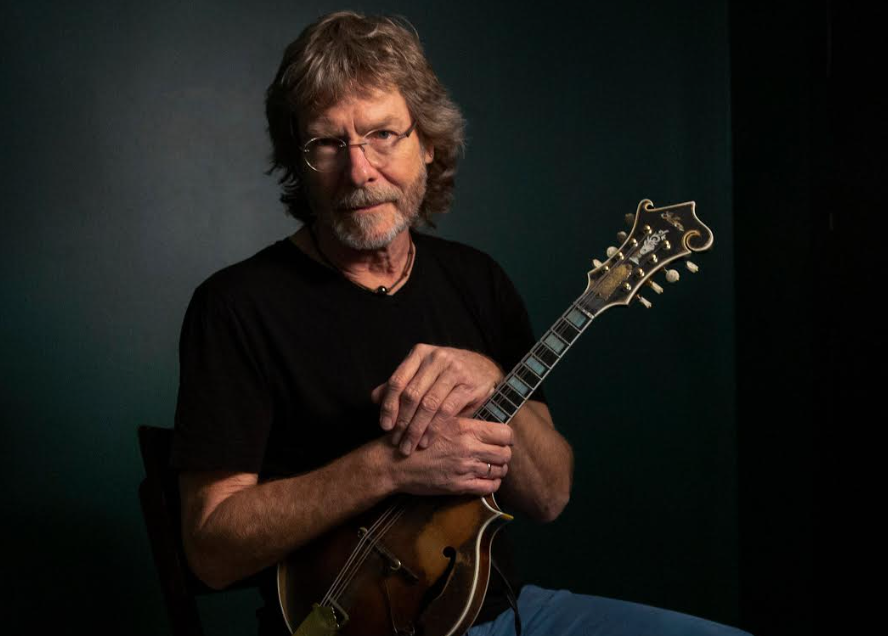

Sam Bush

There was only one prize-winning teenager carrying stones big enough to say thanks, but no thanks to Roy Acuff. Only one son of Kentucky, finding a light of inspiration from Bill Monroe and his Blue Grass Boys, and catching a fire from Bob Marley and The Wailers. Only one progressive hippie allying with like-minded conspirators, rolling out the New Grass revolution, and then leaving the genre’s torch-bearing band behind as it reached its commercial peak. There is only one consensus pick of peers and predecessors, of the traditionalists, the rebels, and the next gen devotees. Music’s ultimate inside outsider. Or is it outside insider? There is only one Sam Bush.

On a Bowling Green, Kentucky cattle farm in the post-war 1950s, Bush grew up an only son, with four sisters. His love of music came immediately, encouraged by his parents’ record collection and, particularly, by his father Charlie, a fiddler, who organized local jams. Charlie envisioned his son someday a staff fiddler at the Grand Ole Opry, but a clear day’s signal from Nashville brought to Bush’s television screen a tow-headed boy named Ricky Skaggs, playing mandolin with Flatt and Scruggs, and an epiphany for Bush.

At 11, he purchased his first mandolin. As a teen fiddler Bush was a three-time national champion in the junior division of the National Oldtime Fiddler’s Contest. He recorded an instrumental album, Poor Richard’s Almanac as a high school senior, and in the spring of 1970 attended the Fiddlers Convention in Union Grove, NC. There, he heard the New Deal String Band, taking notice of their rock-inspired brand of progressive bluegrass. Acuff offered him a spot in his band. Bush politely turned down the country titan. It was not the music he wanted to play. He admired the grace of Flatt & Scruggs, loved Bill Monroe—even saw him perform at the Ryman—but he’d discovered electrified alternatives to tradition in the Osborne Brothers, and manifest destiny in The Dillards.

Bush left home the day after his high school graduation, bound for Los Angeles. He got as far as his nerve would take him—Las Vegas—then doubled back to Bowling Green. “I started working at the Holiday Inn as a busboy,” Bush recalls. “Ebo Walker and Lonnie Peerce came in one night asking if I wanted to come to Louisville and play five nights a week with the Bluegrass Alliance. That was a big, ol’ ‘Hell yes, let’s go.’” Bush played guitar in the group, then began playing mandolin after recruiting guitarist Tony Rice to the fold. Following a fallout with Peerce in 1971, Bush and his Alliance mates—Walker, Courtney Johnson, and Curtis Burch—formed the New Grass Revival, issuing the band’s debut, New Grass Revival. Walker left soon after, replaced temporarily by Butch Robins, with the quartet solidifying around the arrival of bassist John Cowan. “There were already people that had deviated from Bill Monroe’s style of bluegrass,” Bush explains. “If anything, we were reviving a newgrass style that had already been started. Our kind of music tended to come from the idea of long jams and rock & roll songs.” Shunned by some traditionalists, New Grass Revival played bluegrass fests slotted in late-night sets for the “long-hairs and hippies.”

Quickly becoming a favorite of rock audiences, they garnered the attention of Leon Russell, one of the era’s most popular artists. Russell hired New Grass as his supporting act on a massive tour in 1973 that put the band nightly in front of tens of thousands. At tour’s end, it was back to headlining six nights a week at an Indiana pizza joint. But, they were resilient, grinding it out on the road. And in 1975 the Revival first played Telluride, Colorado, forming a connection with the region and its fans that has prospered for 45 years. Bush was the newgrass commando, incorporating a variety of genres into the repertoire. He discovered a sibling similarity with the reggae rhythms of Marley and The Wailers, and, accordingly, developed an ear-turning original style of mandolin playing. The group issued five albums in their first seven years, and in 1979 became Russell’s backing band. By 1981, Johnson and Burch left the group, replaced by banjoist Béla Fleck and guitarist Pat Flynn. A three-record contract with Capitol Records and a conscious turn to the country market took the Revival to new commercial heights. Bush survived a life-threatening bout with cancer, and returned to the group that’d become more popular than ever. They released chart-climbing singles, made videos, earned GRAMMY nominations, and, at their zenith, called it quits. “We were on the verge of getting bigger,” recalls Bush. “Or maybe we’d gone as far as we could. I’d spent 18 years in a four-piece partnership. I needed a break. But, I appreciated the 18 years we had.”

Bush worked the next five years with Emmylou Harris’ Nash Ramblers, then a stint with Lyle Lovett. He took home three-straight IBMA Mandolin Player of the Year awards, 1990-92, (and a fourth in 2007). In 1995 he reunited with Fleck, now a burgeoning superstar, and toured with the Flecktones, reigniting his penchant for improvisation. Then, finally, after a quarter-century of making music with New Grass Revival and collaborating with other bands, Sam Bush went solo. He’s released seven albums and a live DVD over the past two decades. In 2009, the Americana Music Association awarded Bush the Lifetime Achievement Award for Instrumentalist. Punch Brothers, Steep Canyon Rangers, and Greensky Bluegrass are just a few present-day bluegrass vanguards among so many musicians he’s influenced. His performances are annual highlights of the festival circuit, with Bush’s joyous perennial appearances at the town’s famed bluegrass fest earning him the title, “King of Telluride.” “With this band I have now I am free to try anything. Looking back at the last 50 years of playing newgrass, with the elements of jazz improvisation and rock & roll, jamming, playing with New Grass Revival, Leon, and Emmylou; it’s a culmination of all of that,” says Bush. “I can unapologetically stand onstage and feel I’m representing those songs well.”

There was only one prize-winning teenager carrying stones big enough to say thanks, but no thanks to Roy Acuff. Only one son of Kentucky, finding a light of inspiration from Bill Monroe and his Blue Grass Boys, and catching a fire from Bob Marley and The Wailers. Only one progressive hippie allying with like-minded conspirators, rolling out the New Grass revolution, and then leaving the genre’s torch-bearing band behind as it reached its commercial peak. There is only one consensus pick of peers and predecessors, of the traditionalists, the rebels, and the next gen devotees. Music’s ultimate inside outsider. Or is it outside insider? There is only one Sam Bush.

On a Bowling Green, Kentucky cattle farm in the post-war 1950s, Bush grew up an only son, with four sisters. His love of music came immediately, encouraged by his parents’ record collection and, particularly, by his father Charlie, a fiddler, who organized local jams. Charlie envisioned his son someday a staff fiddler at the Grand Ole Opry, but a clear day’s signal from Nashville brought to Bush’s television screen a tow-headed boy named Ricky Skaggs, playing mandolin with Flatt and Scruggs, and an epiphany for Bush.

At 11, he purchased his first mandolin. As a teen fiddler Bush was a three-time national champion in the junior division of the National Oldtime Fiddler’s Contest. He recorded an instrumental album, Poor Richard’s Almanac as a high school senior, and in the spring of 1970 attended the Fiddlers Convention in Union Grove, NC. There, he heard the New Deal String Band, taking notice of their rock-inspired brand of progressive bluegrass. Acuff offered him a spot in his band. Bush politely turned down the country titan. It was not the music he wanted to play. He admired the grace of Flatt & Scruggs, loved Bill Monroe—even saw him perform at the Ryman—but he’d discovered electrified alternatives to tradition in the Osborne Brothers, and manifest destiny in The Dillards.

Bush left home the day after his high school graduation, bound for Los Angeles. He got as far as his nerve would take him—Las Vegas—then doubled back to Bowling Green. “I started working at the Holiday Inn as a busboy,” Bush recalls. “Ebo Walker and Lonnie Peerce came in one night asking if I wanted to come to Louisville and play five nights a week with the Bluegrass Alliance. That was a big, ol’ ‘Hell yes, let’s go.’” Bush played guitar in the group, then began playing mandolin after recruiting guitarist Tony Rice to the fold. Following a fallout with Peerce in 1971, Bush and his Alliance mates—Walker, Courtney Johnson, and Curtis Burch—formed the New Grass Revival, issuing the band’s debut, New Grass Revival. Walker left soon after, replaced temporarily by Butch Robins, with the quartet solidifying around the arrival of bassist John Cowan. “There were already people that had deviated from Bill Monroe’s style of bluegrass,” Bush explains. “If anything, we were reviving a newgrass style that had already been started. Our kind of music tended to come from the idea of long jams and rock & roll songs.” Shunned by some traditionalists, New Grass Revival played bluegrass fests slotted in late-night sets for the “long-hairs and hippies.”

Quickly becoming a favorite of rock audiences, they garnered the attention of Leon Russell, one of the era’s most popular artists. Russell hired New Grass as his supporting act on a massive tour in 1973 that put the band nightly in front of tens of thousands. At tour’s end, it was back to headlining six nights a week at an Indiana pizza joint. But, they were resilient, grinding it out on the road. And in 1975 the Revival first played Telluride, Colorado, forming a connection with the region and its fans that has prospered for 45 years. Bush was the newgrass commando, incorporating a variety of genres into the repertoire. He discovered a sibling similarity with the reggae rhythms of Marley and The Wailers, and, accordingly, developed an ear-turning original style of mandolin playing. The group issued five albums in their first seven years, and in 1979 became Russell’s backing band. By 1981, Johnson and Burch left the group, replaced by banjoist Béla Fleck and guitarist Pat Flynn. A three-record contract with Capitol Records and a conscious turn to the country market took the Revival to new commercial heights. Bush survived a life-threatening bout with cancer, and returned to the group that’d become more popular than ever. They released chart-climbing singles, made videos, earned GRAMMY nominations, and, at their zenith, called it quits. “We were on the verge of getting bigger,” recalls Bush. “Or maybe we’d gone as far as we could. I’d spent 18 years in a four-piece partnership. I needed a break. But, I appreciated the 18 years we had.”

Bush worked the next five years with Emmylou Harris’ Nash Ramblers, then a stint with Lyle Lovett. He took home three-straight IBMA Mandolin Player of the Year awards, 1990-92, (and a fourth in 2007). In 1995 he reunited with Fleck, now a burgeoning superstar, and toured with the Flecktones, reigniting his penchant for improvisation. Then, finally, after a quarter-century of making music with New Grass Revival and collaborating with other bands, Sam Bush went solo. He’s released seven albums and a live DVD over the past two decades. In 2009, the Americana Music Association awarded Bush the Lifetime Achievement Award for Instrumentalist. Punch Brothers, Steep Canyon Rangers, and Greensky Bluegrass are just a few present-day bluegrass vanguards among so many musicians he’s influenced. His performances are annual highlights of the festival circuit, with Bush’s joyous perennial appearances at the town’s famed bluegrass fest earning him the title, “King of Telluride.” “With this band I have now I am free to try anything. Looking back at the last 50 years of playing newgrass, with the elements of jazz improvisation and rock & roll, jamming, playing with New Grass Revival, Leon, and Emmylou; it’s a culmination of all of that,” says Bush. “I can unapologetically stand onstage and feel I’m representing those songs well.”

MORE INFORMATION

This program is made possible thanks to the generous support of Susan Bay Nimoy, Estate of Douglas M. Matheson, Seedlings Foundation, Howard Gilman Foundation, MacMillan Family Foundation, The Shubert Foundation, Blanchette Hooker Rockefeller Fund, Charina Endowment Fund, The Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, PECO Foundation, Coastal Community Foundation of South Carolina, Mustang Foundation, Michael Tuch Foundation, Jody and John Arnhold and the Arnhold Foundation, The Grodzins Fund, and The Isambard Kingdom Brunel Society of North America.

This program is also made possible with public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Kathy Hochul and the New York State Legislature, and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council.

Music programming also receives support from an endowment established by The Bydale Foundation, Mary Flager Cary Charitable Trust, The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation, Christopher and Barbara Dixon, the Herman Goldman Foundation, William and Angela Haines, Walter and Marge Scheuer, and Zabar’s.

Symphony Space thanks our generous supporters, including our Board of Directors, Producers Circle, and members, who make our programs possible with their annual support.

Kathy Landau Executive Director

Peg Wreen Managing Director

Isaiah Sheffer*

Co-Founder and Co-Artistic Director (1978-1988)

Artistic Director (1988-2010)

Founding Artistic Director (2010-2012)

Allan Miller

Co-Founder and Co-Artistic Director (1978-1988)

Darren Critz Director of Performing Arts Programs

*in memoriam